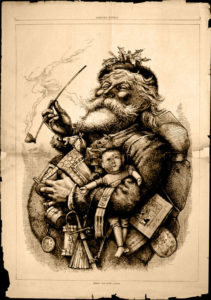

The modern version of Santa Claus did not exist until 1823, when Clement C. Moore penned his poem A Visit from St. Nicholas, which we know better as Twas the Night Before Christmas and was written in Troy, NY. Cartoonist Thomas Nast helped immortalize Santa as the jolly bearded man we recognize with his 1863 illustration in Harper’s Weekly.

Christmas was celebrated over twelve days, beginning on December 25th, and lasted through Epiphany/Twelfth Night (January 6th). Nowadays, the Christmas season seems to begin right after Halloween and ends with Christmas dinner.

Most of the Christmas traditions we hold today have their roots in the Victorian era. Christmas trees, while popular in Germany and other parts of Europe, did not catch on in England and America until 1848, when the Illustrated London News printed a picture of Queen Victoria and her German Prince Albert in front of their Christmas tree. Simple decorations made from evergreens, berries, and other natural materials no longer sufficed. Victorian housewives were instructed by magazines to aid in the creation of elaborate household decorations. Gifts, which once consisted of fruits, nuts, sweets, and homemade trinkets hung on the tree, evolved into larger store-bought gifts that were placed under the tree. Victorian Christmases revolved around the family, much like modern Christmas celebrations. Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol helped to promote Christmas as a time of family, charity, goodwill, peace, and happiness.

The way the Watervliet Shakers celebrated Christmas also evolved over the years, though the Victorian trappings did not seem to catch on until the early 20th century. Early Shaker journals do not always mention Christmas. The entries that do address the holiday usually only recount the religious exercises of the day. One of the more descriptive entries was written by David A. Buckingham in 1855: “This being the day on which our Savior was born, as generally supposed and as record declares, we keep it in commemoration of him in the manner customary heretofore by attending meeting at 9am, read some 2 or 3 chapters of Holy Wisdom’s instruction, exercised some number of songs, strove to rid ourselves of dissention and hard feelings, and rendered our gifts to the poor.” Meeting, remembering the poor, and a good meal seemed to be the norm for Christmas at Watervliet until the 1890s.

In the last decade of the 19th century, Christmas celebrations started to resemble those of the rest of society. The South Family journal from 1894 records Christmas candy making and the crafting of Christmas presents, as well as “entertainment” at the Church Family on the 25th. The South Family even had a Christmas tree the following year. Anna Goepper of the South Family writes about the “school entertainment” in 1915, which seems to be a type of pageant put on by the students. Christmas celebrations included gift exchange (gifts were also sent from non-Shaker neighbors and friends), elaborate decorations and Christmas trees, one of the Shaker girls dressed as Santa Claus, and a Christmas shop in which items were sold to the world’s people for gift-giving. The Shakers always ate well, but the Christmas meal became something special and included fruit cake and candy. The evening was finished with music from the Victrola.

The decline of Shakerism meant that rules became more lax, as there were fewer members of the ministry to enforce them. Christmas celebrations were no exception, and the influence of secular holiday traditions is obvious in the later journals from the South Family, whose closure in 1938 marked the end of the Shaker community in Albany.