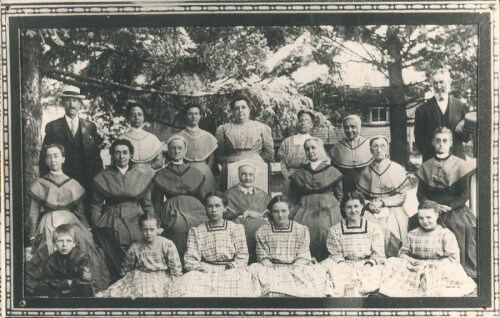

Anna first joined the Shakers when she was just shy of eight years old. Her father, Leopold, was a German immigrant and divorcee. He brought Anna, along with his five-year-old son Maximillian, with him to the community at Union Village, Ohio in 1878. Anna’s mother was born in Wurttemberg, Germany. The Goeppers were not the only German family to become Shakers; there were several German members at Watervliet (four German-language documents from this community are held in the Shaker Collection at the New York State Library). Maximillian would eventually leave the Shakers at sixteen years old, but Leopold and Anna remained life-long Shakers. Both held positions of leadership within the community: Leopold is listed as having been Head Elder at some point, and Anna served as Deaconess in 1896. In the 1908 census, Anna was listed as the youngest Shaker of sixteen women and twelve men.

Anna left Union Village and was living in Watervliet by April 1915. Her father died that December, and Union Village would eventually close its doors for good in 1920. Anna’s first entry in the South Family Journal was on April 5, 1915. Her skills in the kitchen kept her primarily on that duty; she did not rotate to other jobs monthly like others did. Instead, she would receive 2-3 weeks’ vacation from kitchen duty once or twice year and assigned to another task. Anna’s kitchen achievements did not go unnoticed. On June 23, 1916, she recorded: “Have received several grand compliments from different outsiders lately on my baking – my bread, pie, and cake – but it did not swell my head one bit. That gift, I know, is inherited for no one could beat my mother in domestic work.” (This short line is the only other information we currently have about Anna’s mother.) But Anna was generous with praise, too. When Eldress Anna Case was assigned cooking duty that September, Anna gushed that they were “living high for Eldress Anna is a No. 1 fine cook.”

Kitchen work was demanding, but satisfying. As the baker, Anna was responsible for nourishing her brothers and sisters. She recorded that she made 1,560 loaves of bread a year, weighing 2 ½ pounds each. The South Family spent $154 on flour one year, but if they had purchased pre-made bread at 12 cents a loaf for nine, one pound loaves a day (“skimpy,” Anna thinks), they would spend over $393. “From this flour also make pie, cake, and biscuits,” Anna wrote, “20-25 pies a week in summer, 35 a week in winter, 2 meals of cake a week and plenty of muffins and biscuits.” In 1920, she mentions that she baked for 30-33 people.

Anna also noted occurrences in other families. The Church Family rebuilt their barn complex after a destructive fire in 1914. Construction was completed the following year, and a barn raising on May 20th was recorded in Anna’s South Family Journal: “Barn raising at Church Family. Frieda [Sipple] and Grace [Dahm] went up to help in the dining rooms, Grace at the Office and Frieda at the Dwelling House. They fed 23 men to for dinner at Office and 49 at Dwelling. Elder Josiah treated the men to cigars, 3 and 4 each. South Family provided asparagus and butter. In afternoon, all of SF [South Family] except Deborah [Knight] and Anna G[oepper] went to watch . . . Everything went very smoothly.” Because of her record keeping, the Society was able to learn the exact date of the barn raising, as well as what transpired during the event; we are celebrating the centennial this year.

Although the Shakers lived in communities separate from “the World,” they were not immune to the problems of the world outside their communities. As things heated up in World War I, the Shakers began to feel the effects. As head baker, Anna probably noticed it the most: “It is predicted flour will be $14 per bbl before winter is over,” she wrote on October 28, 1916, “for so much wheat is going to Europe.” The Shakers played their part in the war effort by purchasing Liberty Bonds and participating in the voluntary food conservation suggested by Herbert Hoover, who was serving as US Food Administrator at the time. Critics of the effort called it “Hooverizing.” In the spring of 1918, Anna was using something called “Liberty flour,” along with rolled oats, barley flour, and graham flour to make bread. Again, Anna’s baking prowess is evident: “Everybody says my bread is A No. 1, they eat it just as well as the white.” Some of the sisters at the North and Church Families couldn’t quite get the hang of it, though, and they came to Anna for help and advice. The Shakers were also generous with their charity and donated money and much-needed items to the Red Cross.

Anna’s journals are strewn with her opinions of her fellow Shakers, and through them we can get an idea of some of the other personalities living at the South Family. One sister, Joanna Myer, complained of being “heavily charged with electricity” by a thunderstorm. Although it is not known what Anna’s voice sounded like, one can almost imagine her tone when she wrote: “I told Maggie if the Lord would only charge her with a little spunk, ginger, and mustard it would be a good job.” When another sister left the kitchen to “rest up a while,” Anna was relieved to have a “rest and a change from her abomination cooking and nerves, as she calls it, but everybody else terms it a mean disposition and temper.”

The seven years’ worth of journals kept by Anna not only teach us about daily life and some of the other Shakers living at the South Family, but also about Anna herself. Her entries range between humorous (“Mary, Grace, and Helen have an awful time to rid rats from the kitchen . . . No poison or trap has worked yet. These rats have had a college education.”) to dreamy (“A beautiful morning, cool, bright, grass heavy with dew. Just such a morning as I would like to take the train or auto and go as far as South America at the least.”) to succinctly informative (“We have finally got into a state of war with Germany. Oh! How deplorable!”) and everything in between. Her personality seeps through the pages and serves to demonstrate the individual personalities within the communal group.

Sister Anna Belle Goepper died in 1937. She did not live to see the passing of her beloved Eldress Anna Case in 1938, which brought the last outpost of the Watervliet Shakers to a close. Goepper is buried in the cemetery here at Watervliet.