Ed. Note: This is part 3 of a 4 part series. To read part one, please click here. To read part two, click here.

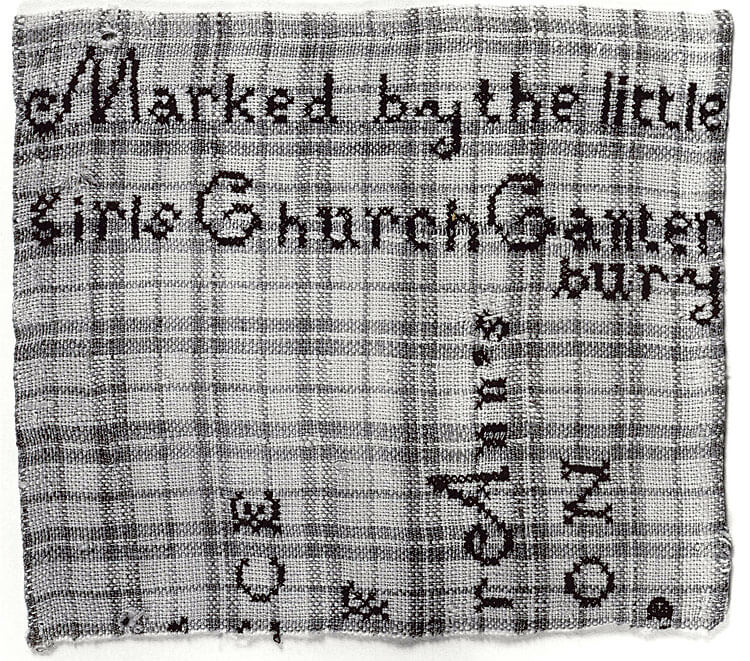

The next category of artifacts that we will explore are textiles related to Ann Lee. The only artifacts that could possibly have belonged to Ann Lee (that I know of) are a handful of apron fragments. Two of these fragments are held in the collection of the Shaker Museum Mt. Lebanon. Both of these are made from blue and white checked linen. The linen is hand spun and the blue color is derived from vegetable dyes that could have been used in the 18th century. Both of the fragments have embroidery made from commercially produced thread that was only available at least 50 years after Ann Lee died in 1784. One is stitched with the words, “Manufactured in England 1774. A remnant of an apron once worn by” with the words cut off. The other textile fragment in the Mt. Lebanon collection is cross stitched as well with the words, “Marked by the little girls Church Canterbury.” It too is cut off with only parts of the words, “Mother Ann’s Apron” still intact.

When I visited the last active Shaker community in Sabbathday Lake, Maine, I asked Brother Arnold Hadd if the Shaker family had any items related to Ann Lee that were not part of their museum collection. He brought out a dusty, yellow manila envelope that held yet another apron fragment. Like the others, it was constructed in a manner that could have dated to the 18th century. This was only the third item that I located that could possibly have been owned by Ann Lee, but surely there are other parts of these aprons since at some point, they were cut up and framed. It seems likely that they were distributed to other Shaker communities or specific individuals. I did find several other “apron” fragments but there was no specific evidence that linked these items to Ann Lee and they most likely dated to a later era. Other textiles that I discovered are recorded as having an association with Ann Lee but have inaccurate documentation related to them. This includes textile fragments at Fruitlands Museum, Hancock Shaker Village, and Canterbury Shaker Village that are cataloged as apron fragments but look more like parts of a rug. I have yet to determine the origins of these fragments or their use but they clearly are utilitarian textiles and not dress fabrics, as noted in the museum records.

Aprons are commonly associated with motherhood, so it seems appropriate that these are the items that we can most conclusively link to the elusive Mother Ann Lee. Jean Humez published an account by Jemima Blanchard in her book, Mother’s First Born Daughters. Referring to a new Shaker convert, Jemima recalled that “She saw hell open, and she seemed to be on the brink in imminent danger of falling. In her efforts to keep out of it, she crept around the room on her hands and knees uttering the most heartrending cries. Mother stooped to her and in her agony wringing her hands, she got hold of Mother’s apron. She knew not what it was or that Mother was near her but it felt like a comfort and support to her, so she kept winding it around her hands.”

Perhaps the most surprising moment during my research trip was when Brother Arnold shared the apron fragment that was stored in the dusty envelope. It clearly was not treated like a sacred relic, yet I know that the Shakers still revere Mother Ann. Brother Arnold speaks eloquently about the life of Mother Ann and her role in the Shaker world. This is no surprise since Shakers still regard Mother Ann as the person who opened the door to the Christ spirit so that it might dwell within their church. Even this aspect of Ann Lee has been confused over time. Some have the incorrect assumption that Ann Lee saw herself as the second incarnation of Christ. Today’s Shakers clarify their beliefs on their website: “Mother Ann was not Christ, nor did she claim to be. She was simply the first of many Believers wholly imbued by His spirit, wholly consumed by His love. Mother’s attitude toward her own role is related more than once in her own recorded sayings. ‘It is not I that speaks; it is Christ who dwells in me,’ she says, testifying both to the indwelling of Christ and her subservience to Him. The closeness of her bond to Him whom she ever called her Lord and Savior is reflected by her having said, ‘I have been walking with Christ in heavenly union. Christ is ever with me, both in sitting down and in rising up; in going out and in coming in. If I walk in groves and valleys, there He is with me and I converse with Him as one friend converses with another, face to face.’ She solves conclusively the question of her own role when she remarks at Ashfield, ‘The second appearing of Christ is in His Church.’”

Written by Starlyn D’Angelo