Americans sprang into action on the homefront and supported the war effort in a number of different ways. You might be surprised to learn that the Shakers, who were pacifists, played their part as well.

Living in their own communities separate from “the World,” the Shakers generally did not involve themselves with worldly concerns. They did not vote or serve in the military, but there were certain issues that they took special interest in; this was especially true in cases of immorality. For example, there are references in the journals to the Shakers at Watervliet assisting fugitive slaves as part of the Underground Railroad. Antoinette Doolittle and Catherine Allen, Shaker sisters both living at the North Family at Mount Lebanon, NY, were advocates for women’s rights. Allen spearheaded a petition drive for women’s suffrage, and in 1825, male and female Shakers at Mount Lebanon took time out of their workday to sign it. Large scale world events permeated the boundaries of Shaker communities. On April 5, 1917, Sister Anna Goepper, who lived in the South Family at Watervliet, recorded in the journal: “We have finally got into a state of war with Germany. Oh! how deplorable!” Goepper’s journal entries during this period give us a glimpse into what wartime life was like for the Shakers in Watervliet.

As pacifists, the Shakers were exempt from military duty, a privilege they secured during the Civil War. Even though Shaker brethren were not being drafted and sent to Europe, the war did affect daily life, just as it did for every other American citizen on the home front. Every day items became harder to secure due to shortages and rising prices. Goepper writes: “Eldress Anna [Case] is planning to buy 5 barrels of Gold Medal flour before it gets any higher. It is predicted flour will be $14 per bbl [barrel] before winter is over for so much wheat is going to Europe.” In 1918, Goepper records that she has come up with a clever substitute for regular flour. By using some “liberty flour,” part rolled oats and part barley flour, and graham flour, she bakes loaves. “No more entirely white bread,” she writes. “Going to soldiers. Everybody says my bread is A No. 1, they eat it just as well as the white.” Sisters from the North and Church Families came to her for guidance, since they didn’t seem to be having much luck with the substitute ingredients.

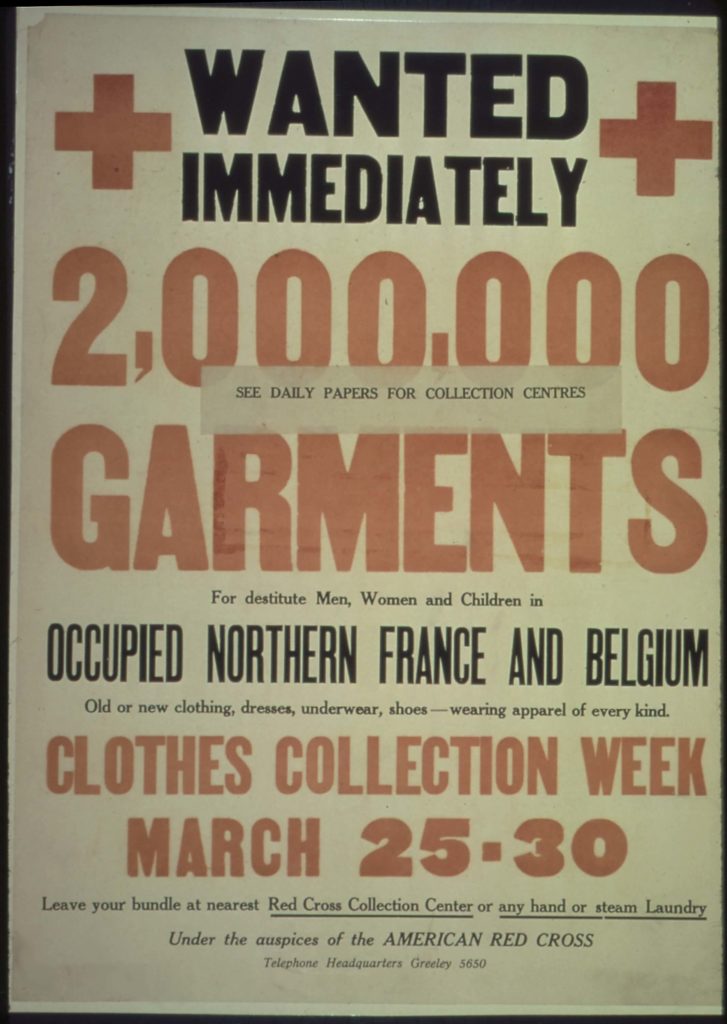

Even though the Shakers weren’t donning uniforms, they played their part in the war in other ways. The government encouraged the purchase of Liberty Bonds to help finance the war. Eldress Anna purchased a $150 Bond. Eldress Caroline [Late] bought one as well and Elder Josiah [Barker] bought several. They were also heavily involved in charity work, as they always were. The items were being sent to the Belgian refugees who escaped their neutral country after Germany invaded in 1914. Future president Herbert Hoover created the Commission for Relief in Belgium, which worked with Britain’s War Refugees Committee (WRC) and the Secours National, to help Belgian refugees and those still trapped inside the country. Posters calling for donations of clothing appeared across the country. The Shakers answered this call with gusto. “Everybody that can is busy knitting, crocheting, and sewing,” Goepper reports on January 22, 1919. “Folks doing a lot of Red Cross work. Made 30 outing shirts and 4 large heavy square shawls knit and crocheted to be sent to the Belgians. Our family have done a great amount of Red Cross work which of course is free, also Eldress Anna has given and donated a vast amount in clothes, woolen goods, and money.” This wasn’t the only entry concerning the Red Cross work they did to help with the refugee relief effort; Goepper mentions it twice more over the next two months. In 1918, the War Department asked to rent some of the West Family buildings for sick and dying soldiers. Goepper notes that “they offer good pay.”

Even though the Shakers weren’t donning uniforms, they played their part in the war in other ways. The government encouraged the purchase of Liberty Bonds to help finance the war. Eldress Anna purchased a $150 Bond. Eldress Caroline [Late] bought one as well and Elder Josiah [Barker] bought several. They were also heavily involved in charity work, as they always were. The items were being sent to the Belgian refugees who escaped their neutral country after Germany invaded in 1914. Future president Herbert Hoover created the Commission for Relief in Belgium, which worked with Britain’s War Refugees Committee (WRC) and the Secours National, to help Belgian refugees and those still trapped inside the country. Posters calling for donations of clothing appeared across the country. The Shakers answered this call with gusto. “Everybody that can is busy knitting, crocheting, and sewing,” Goepper reports on January 22, 1919. “Folks doing a lot of Red Cross work. Made 30 outing shirts and 4 large heavy square shawls knit and crocheted to be sent to the Belgians. Our family have done a great amount of Red Cross work which of course is free, also Eldress Anna has given and donated a vast amount in clothes, woolen goods, and money.” This wasn’t the only entry concerning the Red Cross work they did to help with the refugee relief effort; Goepper mentions it twice more over the next two months. In 1918, the War Department asked to rent some of the West Family buildings for sick and dying soldiers. Goepper notes that “they offer good pay.”

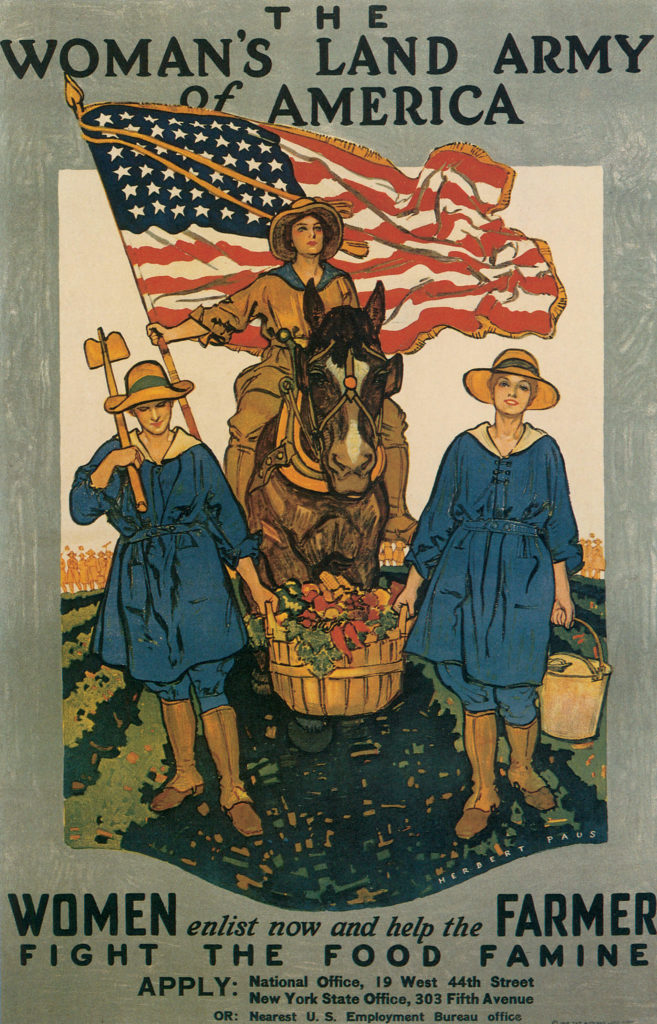

Perhaps the most interesting way the Shakers assisted, however, was by renting out the West Family for a group of workers from the Women’s Land Army of America (WLAA), which later became the Women’s Land Army (WLA). The program ran from 1917-1921 (and was revived during WWII), and placed over 20,000 women on farms to work. Many of these “farmerettes” were college educated. Farmerettes were highly trained and very necessary; the farmers had lucrative contracts with the government to provide food for the military, but they could not fulfill these contracts without workers. Because of how badly the farmers needed the laborers, the women were able to secure wages equal to those of male farm laborers, were protected by an 8-hour work day, avoided terrible conditions, and even received some benefits like workman’s compensation insurance and overtime pay. This movement was particularly strong in the west and northeast and was associated with the suffrage movement and some colleges. Goepper mentions the beginning of this arrangement in her journal in the spring of 1918: “Have rented West Family for 5 months at $25 per month for agricultural purposes. Lot of college girls coming.” Goepper approved of this group, apparently, because in June she writes: “The farmerettes get $15 a month and board. They prove to be good workers.” The South Family Shakers worked alongside the farmerettes, who would come over from the West Family to assist. Four Farmerettes helped Eldress Anna and Sisters Mary and Grace Dahm pick beans that July. It seems that the partnership was beneficial to both groups, because the farmerettes returned to the West Family the following summer.

The Shakers’ desire to live separately from the World conflicted with their necessary reliance on it. Some things could not be avoided, and every war in American history touched the lives of Shakers. They did not support World War I, certainly, but their willingness to buy Liberty Bonds and host the farmerettes illustrates their desire to show their patriotism. They were, after all, Americans, and would be just as affected by the outcome as anyone else.