Reprinted from the Winter 2019 edition of the Watervliet Shaker Journal.

Written by Lorraine Weiss

In March, 1866, a young girl of 11 ran away from home in Rochester, New York. Home life was deteriorating after the death of her mother, possibly due to her father’s drinking. A relative managed to send her to the Shakers, where she found not only shelter, but also a spiritual mooring that would last the rest of her life. Her name was Mary Ann Case (later Anna Case), and her arrival at the South Family was noted in a journal entry of March 18, 1866 which reported that “Mary Ann Case believed.”

We know of Mother Ann Lee, who brought the Shakers to Albany and spread the religion to other Northeast communities; and Mother Lucy Wright, who was Lead Minister for 25 years (1796-1821) and whose foresight and administrative skills expanded the network of communities and established the framework of daily life for all Shakers. Anna Case, too, brought compassion, leadership, and administrative skills to the Shakers. However, her story took place at the other end of the narrative, when circumstances forced her to oversee the dissolution of the Watervliet community that Mother Ann and Mother Lucy had created.

Each Shaker Family assigned a member to keep a daily journal and, along with other business records, these occasionally provide information about the activities of individual Shakers. Entries about Anna Case show that she was involved in the typical variety of tasks required of all members of this communal society. Between May and December of 1885, for example, she painted windows of three buildings, helped with harvesting, worked at “spooling” thread, made dresses for “each of the little girls” at the South Family; and “finished weaving three stair carpets.”

Her leadership qualities were recognized by 1881 when she was assigned to assist Eldress Rosetta Hendrickson (1844-1912). The 1905 New York State Census identifies the 48-year old Anna Case as “Eldress” along with Eldress Hendrickson, now 60. It is likely that by this time the role of Elder/Eldress also entailed the duties performed by Deacons/Deaconesses who had managed the day-to-day personnel matters of the community, such as work and residential assignments. Anna Case became lead Eldress in 1912 after Eldress Rosetta’s death. By the Spring of 1915, she was also appointed a Trustee of the Watervliet Shakers, which expanded her work to include managing all business affairs.

The Shakers remained an agricultural community in the 20th century and relied heavily on hired labor. Overseeing farm managers and produce sales would have been part of Eldress Anna’s work. She also arranged for the sales of other wares produced specifically for The World, such as shirts sewn for area shirt factories, sweaters knitted for department stores and various textiles and fancy goods. At the same time, she was procuring the supplies needed for the Shakers themselves. There are references to her coping with the rationing of flour and other items during WWI.

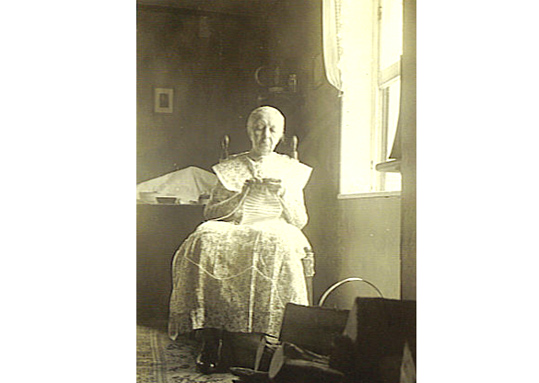

When she wasn’t taking care of her spiritual and administrative responsibilities, Eldress Anna was often at work sewing or knitting and making things for the Sisters’ store, as Anna Goepper notes frequently in the South Family Journals:

“No one can beat Eldress Anna along the line of knit goods of any kind or description. She is busy every moment when she has spare time.” (July, 1916)

“She knits such lovely sweaters, a beautiful needle-worker of all kinds.” (July 8, 1922)

“Eldress Anna is busy all the time knitting silk sweaters perfectly elegant. She gets $40-45 for them. Knits them of fine silk braid that costs $1 a spool. (Sept. 13, 1922)

In December of 1922, Lucy Bowers exclaimed in a diary entry “Eldress Anna knits a sweater in 48 hours or less.” In addition to knitting items for the store, she was also one of the Shaker sisters who produced doll clothes for sale to The World. Goepper notes in 1921 that Anna Case is “dressing 12 dolls for sale in Shaker clothes.”

Eldress Anna’s focus extended far beyond the South Family. Lucy Bowers’ diary entry for July 3, 1919 notes, “Eldress Anna goes with the [Lebanon] Ministry to the North [Family]. Another tortuous move instituted.” She refers to the process of closing the Watervliet North Family. By the time of this diary entry, Anna Case had been involved in closing three communities.

Perhaps the first two closings she witnessed were in the 1890s when members of the Groveland community (near Rochester) and the largely African American Shaker community in Philadelphia were moved to the Watervliet site. In 1915, she had a direct role when the Central Ministry called her to a meeting about closing the Enfield, Connecticut community. She was given the task of moving Lucy Bowers and Eldress Caroline Tate to the South Family.

However, the decline of the Shaker way of life hit closer to home when the Watervliet West Family was closed beginning in 1916. There were several short-term rentals arranged, first as a base for college girls working with the Women’s Land Army of America to help pick crops during WWI, and later as a camp site for a Church. It would be several years before the West and, later, the North Families’ properties sold. Meanwhile, there were many months of work required to clean out buildings, sell furniture and equipment, and renovate buildings to move the remaining Shakers to the South Family.

By 1922, it was clear that the Church Family could no longer be maintained as a separate community. The remaining Sisters were not as cooperative about leaving as those at other sites had been. In a society that relied on governing by consensus, this proved to be a huge stumbling block. In January of 1923, Lucy Bowers reported that there was ”[n]o sign of a sale because all of the sisters pull apart.” The property was finally sold in 1925. South Family members witnessed the transformation of the Church Family site for a Preventorium (for those exposed to, but not ill with tuberculosis), demolition of 20 buildings, construction of the Ann Lee Home, and development of the Albany airport in the late 1920s.

By 1926 there were few children left at the South Family. The Shakers were forced to close the District 14 School, which meant that the remaining children, who were boarders, could no longer live with the Shakers. Eldress Anna had been in charge of overseeing the teachers hired for the school, and also played a large role in the lives of those who spent their early years at the South Family. Martha Hullings, Eleanor Brooks Fairs, and Gertrude Sherburn are among those who had fond memories of a strict, but kind Eldress. She was known as being more lenient in some ways than other Eldresses.This leniency took the form of treating children to a movie and the circus once a year and occasionally allowing toys. The Shaker lifestyle had changed dramatically during Anna Case’s life. The Shakers were never completely isolated from The World due to their economy, and were aware of outside political and cultural events—Anna Case was one of four people who traveled to Albany to see President Grant’s body in 1885. By the 20th century, however, contact with the outside world had expanded. Eldress Anna went on extended trips to visit a niece in Rochester and took day trips with other sisters to Lake George. After Thanksgiving dinner in 1929, she and three other sisters went to see “The Gold Diggers of Broadway” at Albany’s Madison Theater. She maintained outside friendships and business partnerships, and hosted holiday celebrations and picnics as a way of reciprocating hospitality. Forty guests enjoyed boxed lunches and fireworks at her 1924 Fourth of July picnic.

Anna Case overcame several instances of serious illnesses, including an episode of “quinsy” (a throat infection) that began in January of 1890. In March, after months without solid food, the consulting doctor, Dr. Lothridge, diagnosed that she was “threatened with paralysis of heart” and she was treated with the Electro Static Machine, a Shaker invention. She finally returned to work in August. In February 1921, Anna Goepper reported that “Eldress Anna had a stroke at the sewing shop. . .her tongue, face, hands, eye and side were all twisted and numb.” After a few months spent recovering at Hancock, she returned to the South Family where, with the members’ consent, the Ministry had appointed Ella Winship to help her with bookkeeping and other clerical work.

It is not hard to imagine how the stress of overseeing daily operations and the added burden of closing communities would have taken a toll. Anna Goepper lamented “I am afraid her best days are over.” And yet, Eldress Anna continued to work, knit and sew, deal with the Church Family sale, and was noted as putting up chili sauce with Eldress Caroline in 1924. In 1934 she was still traveling as far as Utica to conduct Shaker business.

As she coped with the various economic and social aspects of the dwindling Shaker communities, she was aware of the need to ensure that the history of the Shakers would not also disappear. In October of 1929, Eldress Anna traveled to Pittsfield to see a display of Shaker articles. Her very life was now the object of study. Along with M. Catherine Allen of the Lebanon Ministry, she and others arranged for Shaker archives and objects to be acquired by the New York State Museum and the Case Western Reserve Historical Society.

During Eldress Anna’s visit to Rochester in 1917, Anna Goepper wrote: “We miss dear Eldress Anna very much indeed. There is only one Eldress Anna on this earth in my opinion and there will never be another. She is the best Eldress I have ever known or ever had.” She had touched many other lives in the same way. Notes about her funeral in July, 1938 mention 40 floral pieces and 60 autos. As an Eldress of the Watervliet Shaker Community, Anna Case was buried in the same row of the Shaker cemetery as Mother Ann Lee and Mother Lucy Wright. Hers was the last burial in the cemetery. The few sisters who remained at the South Family at her death, Freida Sipple, Grace Dahm, and Mary Dahm, were moved to Mount Lebanon. Eventually, the South Family property was closed and sold, thus ending the 162-year story of America’s first Shaker settlement.